1871 American attack on Korean forts

By the 1870s Western powers had ventured into Asia and forced most nations to open themselves to trade and diplomatic relations, not always with happy results. The American gunboats that forced Japan to encounter the outside world prompted civil war and a process of modernization; in China the Opium Wars produced more civil war and weakness of the Qing dynasty. One country that was determined to keep closed was Korea, the “Hermit Kingdom”, which forbade most foreign contact.

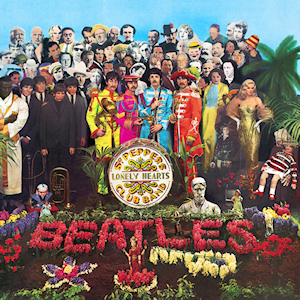

In 1866 the American merchant ship General Sherman attempted to sail deep into Korean territory, ostensibly to trade, but was attacked and the crew killed. An American expedition of their Asiatic Squadron was sent to the peninsula in 1871 to learn more of the fate of the doomed ship and to negotiate treaties with the Korean government. The reply was to refuse talks and to fire on the American fleet, whose commander demanded an apology with 10 days. When that was not forthcoming by June 10, troops were landed and several Korean forts on Gangwha Island were taken at the cost of 3 American dead and 243 Korean casualties. The enormous banner of the commanding officer was captured (see above).

Despite these losses the Korean government refused to negotiate and it was not until 1882 that Korea opened itself up to foreign diplomacy and trade. The flag (the only one of its kind surviving) was returned to Korea in 2015.