1402

The fall of Bayezid the Lightning

In 1402 the Turkish sultan Bayezid I, nicknamed “the Lightning”, could consider himself quite the success. He had seized the throne immediately after the death of his father at the Battle of Kosovo which broke the power of Serbia and had secured his claim by murdering his baby brother — setting the fratricidal example that Turkish leaders would follow for centuries. In 1396 he had smashed a great western crusade at the Battle of Nicopolis and erected the monumental Ulu Cami mosque in celebration. He had crushed other Turkish emirs and forced them to submit to his overlordship — but now he faced a new challenge out of Central Asia: the all-conquering Mongol armies of Timur the Lame (known in the West as Tamerlane).

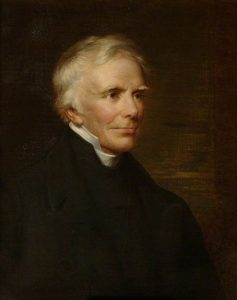

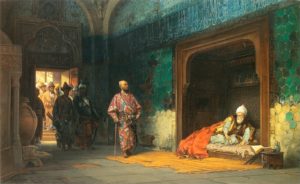

Bayezid had been laying siege to Constantinople, the capital of the shrinking Christian Byzantine empire, but he abandoned that project and headed into the Anatolian heartland with a tired and thirsty army. Instead of allowing the enemy to exhaust himself chasing Turkish forces in the mountains, Bayezid insisted on an attack against a larger army possessing war elephants and mounted archers. The Turks were smashed and Bayezid was carted away by Timur in a cage. He never regained his freedom. (The 19th-century painting above shows Timur examining his captive.)

When Timur, having shattered the work of four Ottoman generations, turned back eastward, the Ottoman lands fell into a fierce internecine struggle among four brothers who contended with each other to secure possession of their European provinces, which had been little affected by the Mongol invasion, and to reunite the Ottoman dominions. In these wholly unexpected circumstances the Byzantines found themselves the favoured allies first of one Turkish contender, then of another. The blockade of Constantinople was lifted. Thessalonica – with Mount Athos and other places – was restored to Byzantine rule, and the payment of tribute to the sultan was annulled. It was the last breathing spell for the Christian empire, occasioned by a battle between two Muslim warlords.