1680

The Pueblo Revolt

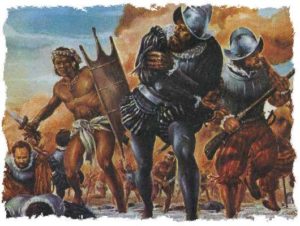

Beginning in the mid-16th century, Spanish troops and settlers penetrated into the territory of the Pueblo in what is now New Mexico. Though royal Spanish law was remarkably tolerant for the time, its enforcement in distant parts of the empire was weak, leading to the enslavement and forced conversion of natives. Franciscan missionaries evangelized the Pueblo and won many to at least a superficial attachment to Christianity but most natives continued various aspects of their traditional spirituality including psychoactive drugs and kachina dances. Drought conditions and raids by the Apache added to the resentment against the Spanish occupiers and prompted a number of local unsuccessful revolts.

In 1680 a Pueblo leader named Popé (or Po’pay) engineered a conspiracy against the Spanish settlers and their missionaries. The notoriously fragmented natives had no tradition of political unity, but such was their hatred of their suppression that they listened to Popé’s blandishments, which promised an end to the drought and a return to prosperity if the foreigners were expelled and the Pueblo returned to the worship of their old gods. On August 10 they rose up en masse and began murdering hundreds of priests and colonists. Columns of frightened Spanish retreated from the territory into the safety of Texas, leaving the Pueblo once again in charge of their destiny. Popé travelled through the land, urging the destruction of all Spanish churches, and buildings, and discouraging the agriculture that the newcomers had brought: the cultivation of fruit trees, wheat and barley, and raising livestock such as cattle and sheep.

For twelve years the Pueblo maintained their independence but the droughts did not end with the return of the old gods, nor did Apache raids cease. When a new Spanish governor invaded again, he promised clemency for the rebels and distributed food; a peace was agreed upon. There would be further outbreaks of violence but, in general conditions, were better and Spanish oppression diminished after the revolt.