Shooting and killing and such on this date

1813 Fort Mims Massacre

In 1813 a war broke out in present-day Alabama between white settlers and an anti-white faction of the Creek tribe, known as the Red Sticks. Vowing revenge for a white militia attack on a Creek pack train at the Battle of Burnt Corn, a 1,000-man force of Red Sticks attacked Fort Mims, which sheltered hundreds of whites, their black slaves, and mixed-race farmers. After storming the gates, a bloody massacre ensued in which about 500 settlers were killed. (The slaves were spared but taken captive). The battle prompted initial panic and an armed response. The climactic Battle of Horseshoe Bend in 1814 resulted in an American victory over the Creeks and gained fame for the victorious general, Andrew Jackson.

1914 Battle of Tannenberg

The German master plan for World War I envisioned first using most of its forces in fighting an offensive war against France on the Western Front, and maintaining a smaller army in the East for a defensive war against the Russian Empire. Once France had been conquered, the German army would then turn on the Russians who, it was believed, would be slower to mobilize. The Russians launched an attack on East Prussia in August 1914 and, at first, succeeded in driving the Germans back. The High Command in Berlin then sacked its military leadership in the East and replaced it with two new generals, Paul von Hindenburg and Erich Ludendorff. With a more aggressive attitude, the two succeeded in smashing the Russians and forcing them out of East Prussia. The fame that this accrued the two led to their achieving a sort of military dictatorship over German from 1916-18. After the war both generals became involved in ultra-nationalist politics; Hindenburg was elected president of the Weimar Republic from 1925-34.

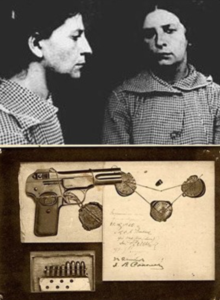

1918 Attempted Assassination of Vladimir Lenin

The Russian Revolution was a battle of coalitions. The Bolshevik wing of the Communist Party, led by Lenin, initially counted on the support of the left wing of the Socialist Revolutionaries but the two factions fell out early in 1918. One Left SR, Fanny Kaplan, who had been jailed under the Tsarist regime for a terrorist plot, approached Lenin as he emerged from a speech and shot at him three times with a pistol. Two bullets struck him in the neck and lung and he was rushed away for treatment. Kaplan told her captors: “My name is Fanya Kaplan. Today I shot Lenin. I did it on my own. I will not say from whom I obtained my revolver. I will give no details. I had resolved to kill Lenin long ago. I consider him a traitor to the Revolution.” She was soon executed by the Cheka, the Bolshevik secret police. This attempt, though a failure, had grave consequences: it prompted the Red Terror and probably hastened the death of Lenin who never quite recovered, leaving the Soviet project in the hands of Joseph Stalin.