St John of Capistrano

“When the swallows come back to Capistrano” was a hit song for the Ink Spots in 1940. What do migrant birds in California have to do with an Italian soldier-saint honoured on this day?

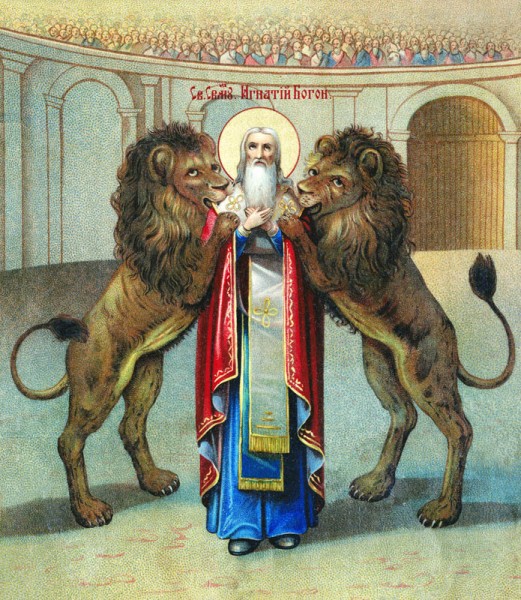

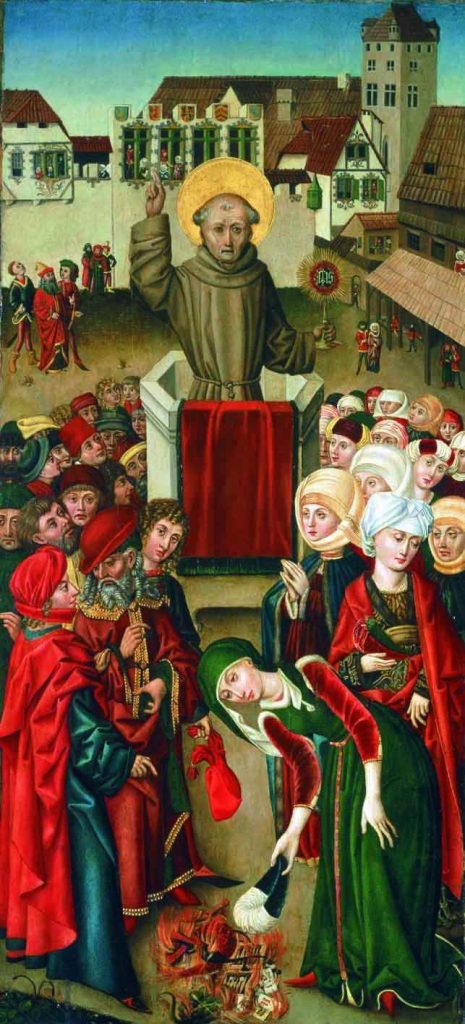

Giovanni da Capestrano (1386-1456) was the son of a nobleman at the court of the King of Naples and was meant for the life of a soldier and administrator. He studied law at Perugia and was named governor of that city in his mid-20s. When war broke out between Perugia and Rimini he was made a prisoner of war. While in jail, he decided to become a priest and set himself to the study of theology. On his release he joined the Franciscan order, where he would always campaign for stricter discipline, and became a well-known itinerant preacher. Many of his fiery sermons were directed against Judaism, inciting cities to expel their Jewish populations. John was also a fierce opponent of the Hussite heresy which had broken out in the Czech lands. He developed a reputation as a miracle worker, curing the sick by making the sign of the cross and walking on water.

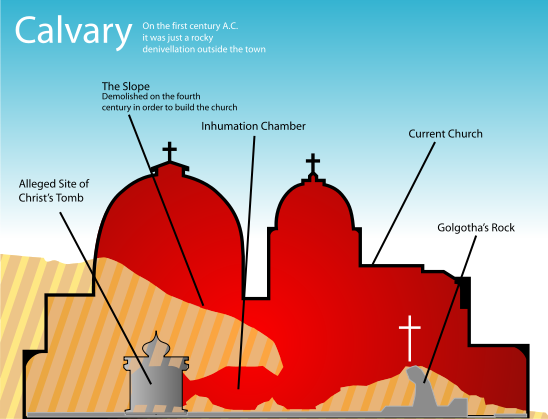

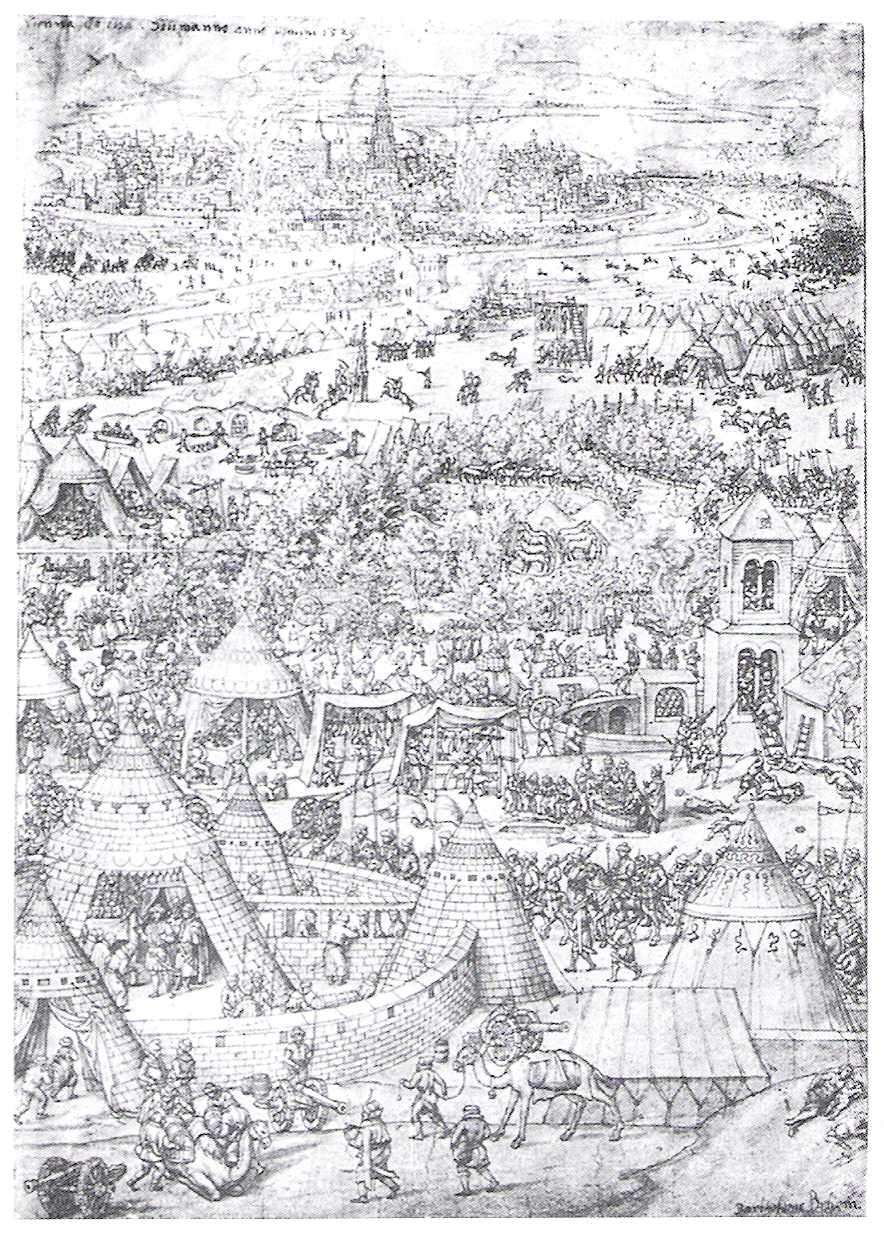

In 1453 the Ottoman Turks under Mehmet the Conqueror captured Constantinople, the last stronghold of the Byzantine, or Eastern Roman, Empire and threatened to press on farther into Christian Europe. John undertook to raise a crusade against the Muslim invaders and with the help of Hungarian general Janos Hunyadi, his army defeated the Turkish siege of Belgrade in 1456. John is said to have personally led troops in attacking the Ottoman lines. He died shortly thereafter of the plague.

John was canonized in 1690 and a number of Franciscan missions in Spanish America were named after him as San Juan Capistrano. His feast day was originally March 28, the date on which migratory swallows return to the area of one of those missions in California. This romantic reunion was celebrated in song by composer Leon René:

When the swallows come back to Capistrano

That’s the day you promised to come back to me.

When you whispered, farewell in Capistrano

Was the day the swallows flew out to the sea.

All the mission bells will ring, the chapel choir will sing

The happiness you bring will live in my memory.

When the swallows come back to Capistrano

That’s the day I pray that you’ll come back to me.

In 1969 the calendar reforms of Pope Paul VI moved John’s feast day from March to October 23, the date of the saint’s death.