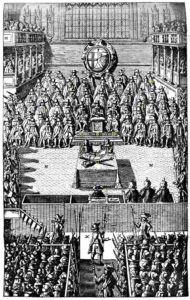

If you were around Westminster in London on this date in 1649 you would have noticed a rare event: a king being put on trial for treason.

Charles I, the second of the Stuart dynasty, had quarrelled with Parliament and had fallen (or jumped) into a bitter Civil War which he and his royalist cause had lost decisively. Now he was being tried for warring against his people and “all the treasons, murders, rapines, burnings, spoils, desolations, damages and mischiefs to this nation, acted and committed in the said wars.”

The king refused to plead, asserting that no one had the power to judge him and that God had commanded sovereigns to be obeyed. The High Court of Justice, acting on behalf of the rump of the Parliament that remained, was unimpressed, found him guilty, and ordered him executed. Fifty-eight commissioners put their signatures on the death warrant, thus becoming known as “regicides” on whom vengeance would be taken when the monarchy was eventually restored.