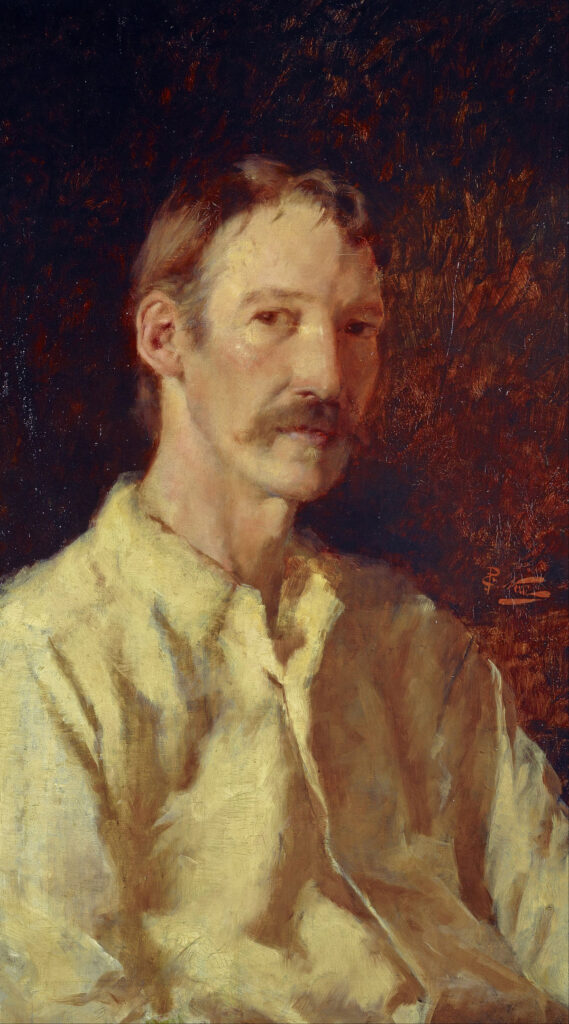

In 1887 the Scottish poet and novelist Robert Louis Stevenson was recovering for a moment from the lung disorder that would eventually kill him. In his convalescence he wrote his “Christmas Sermon”, a melancholy reflection on human striving. Here are a few of the notable passages from it.

To make our idea of morality centre on forbidden acts is to defile the imagination and to introduce into our judgments of our fellow-men a secret element of gusto.

If your morals make you dreary, depend upon it they are wrong. I do not say “give them up,” for they may be all you have; but conceal them like a vice, lest they should spoil the lives of better and simpler people.

To be honest, to be kind — to earn a little and to spend a little less, to make upon the whole a family happier for his presence, to renounce when that shall be necessary and not be embittered, to keep a few friends, but these without capitulation — above all, on the same grim condition, to keep friends with himself — here is a task for all that a man has of fortitude and delicacy. He has an ambitious soul who would ask more; he has a hopeful spirit who should look in such an enterprise to be successful. There is indeed one element in human destiny that not blindness itself can controvert: whatever else we are intended to do, we are not intended to succeed; failure is the fate allotted.

There is an idea abroad among moral people that they should make their neighbors good. One person I have to make good: myself.

In his own life, then, a man is not to expect happiness, only to profit by it gladly when it shall arise: he is on duty here; he knows not how or why, and does not need to know; he knows not for what hire, and must not ask. Somehow or other, though he does not know what goodness is, he must try to be good; somehow or other, though he cannot tell what will do it, he must try to give happiness to others.