Back to precarity. In 17th-century London it was the responsibility of each parish to keep records of births and deaths. The birth part was easy as each child was required to be presented for baptism and its name entered. Here is how the procedure for establishing cause of death worked:

When anyone dies, then either by tolling, or by ringing of a Bell, or by bespeaking of a Grave of the Sexton, the same is known to the Searchers, corresponding with the said Sexton. The Searchers hereupon…examine by what Disease, or Casualty the corps died. Hereupon they make their Report to the Parish-Clerk, and he, every Tuesday night, carries in an Accompt of all the Burials, and Christnings, hapning that Week, to the Clerk of the Hall. On Wednesday the general Accompt is made up, and Printed, and on Thursdays published and dispersed.

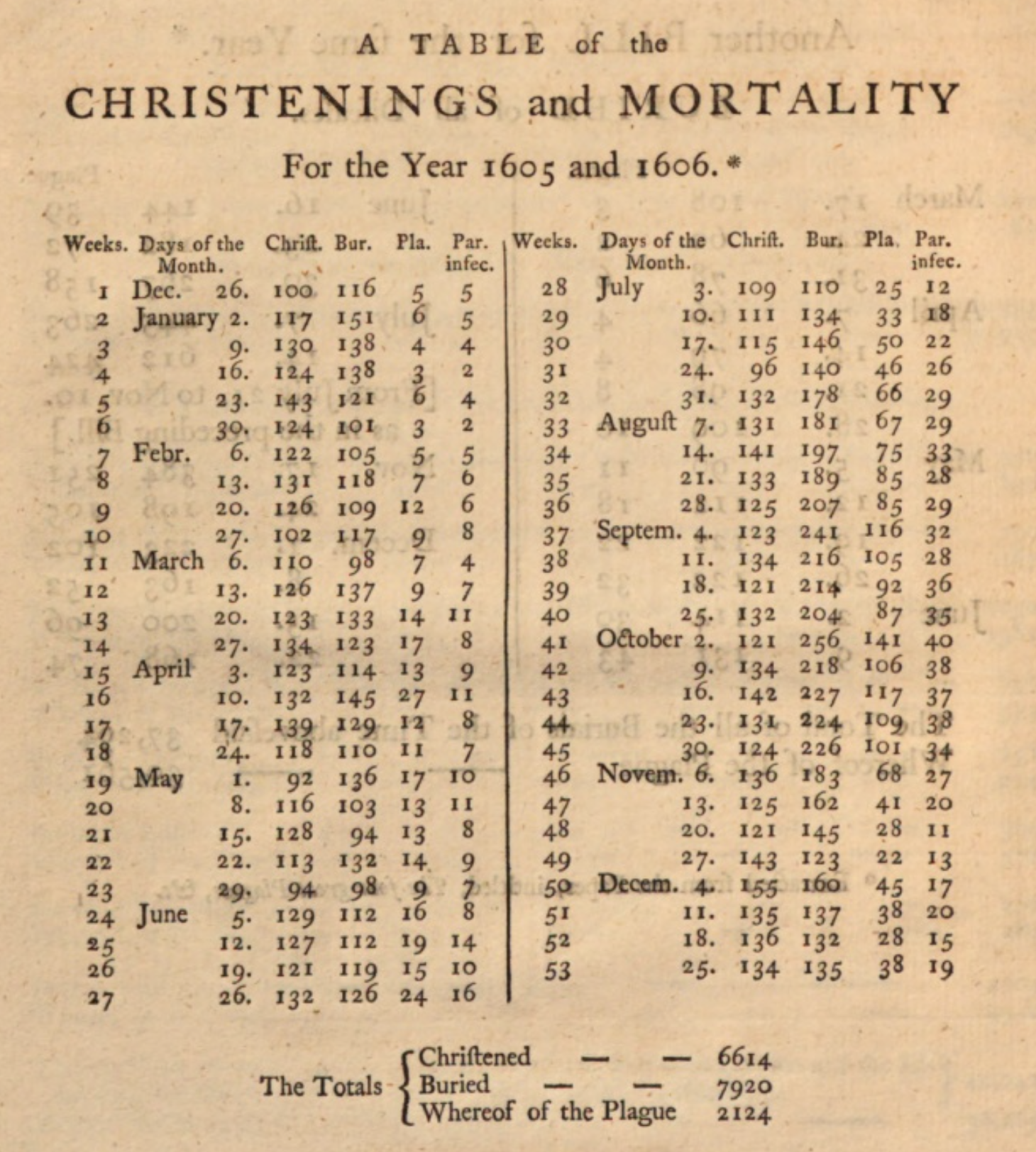

Here is a sample for the years 1605-06. Note that deaths outnumbered births and that deaths caused by the plague were enormous and recorded separately.

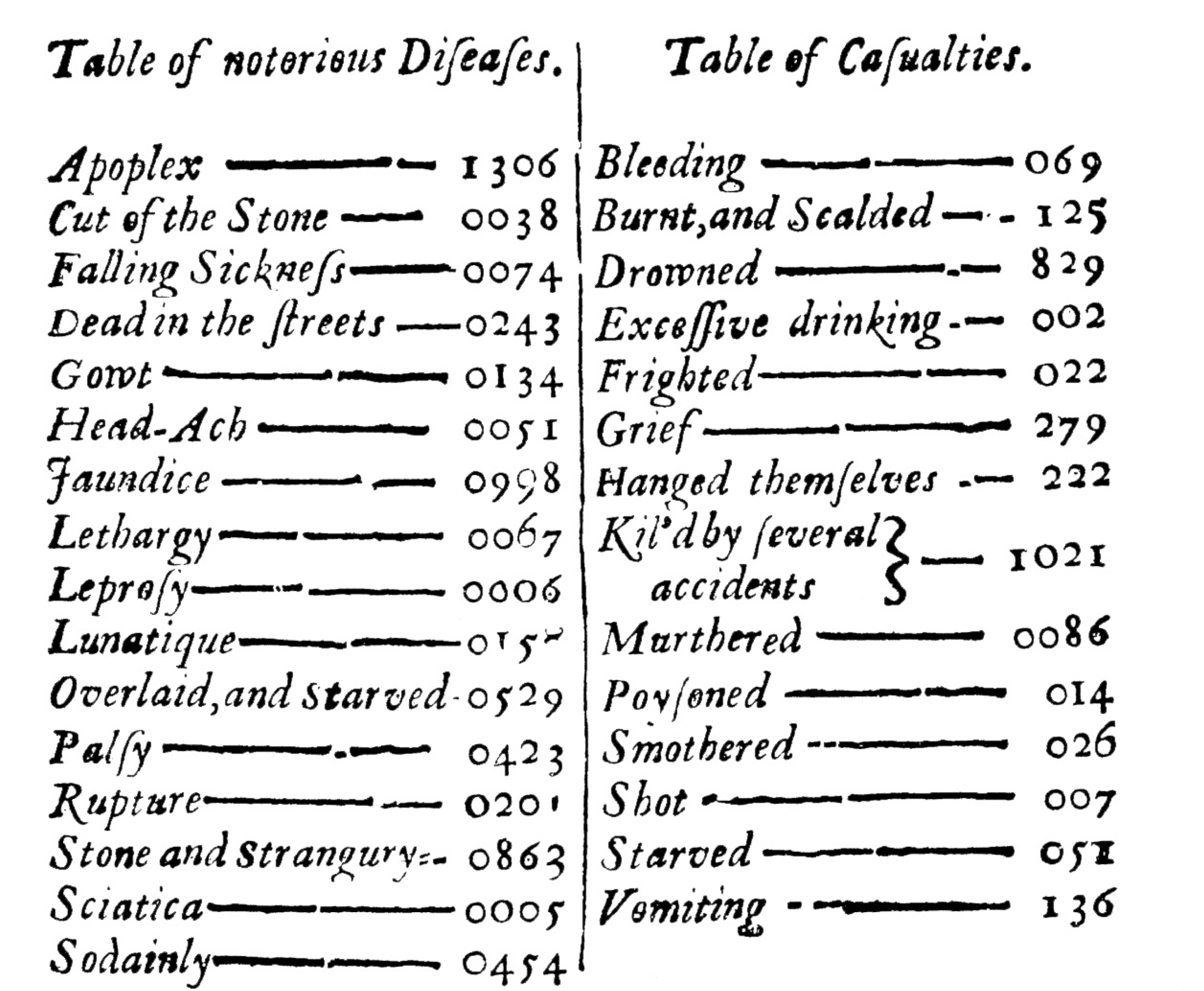

John Graunt, a well-off London haberdasher collected such data for a period of two decades and in 1662 published the world’s first attempt at a demographic survey, Natural and Political Observations, Mentioned in a Following Index, and Made Upon the Bills of Mortality, 1662, by John Graunt, a London haberdasher. Graunt made it his concern to examine two decades worth of parish records and “bills of mortality”. Graunt was skeptical of the Searchers’ accuracy in many cases and used statistical inference to calculate life expectancy and more reliable assessments of the causes of death.

In the 21st century we still die from apoplexy (stroke) and strangury (urinary tract disease) but few of us perish from being “cut of the stone” (operation for removal of gallstones or kidney stones) or leprosy. Note the dreadfully high death rate of “overlaid and starved” — children being smothered while sleeping in bed with adults or dying from lack of nutrition. Graunt blamed this on “the carelessness, ignorance, and infirmity of the Milch-women” (wet-nurses).

Three years after Graunt’s first edition, in 1665, the year of the Great Plague, London bills of mortality showed 97,306 burials, of which 68,598 were deaths from plague.