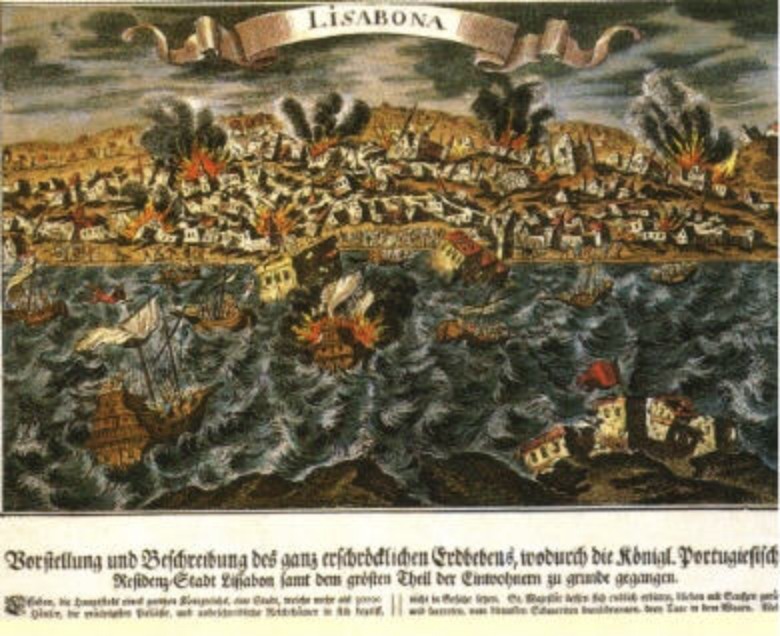

1755 The Lisbon Earthquake

On the morning of November 1, All Saint’s Day, at 9:40, a massive earthquake, followed a tsunami, and a series of devastating fires destroyed the city of Lisbon and wrought havoc on much of the Portuguese coastal area. The quake’s effects were felt as far away as Brazil and Greenland. It is estimated that 40,000-50,000 people may have died with many more injured or homeless.

About 85% of the city was destroyed. Palaces, hospitals, churches, homes and government buildings were obliterated. Precious libraries and art work were lost forever as well as much of the architecture of earlier ages. (Those who find the distinctive Portuguese late Gothic style known as Manueline to be too ugly for words will not rue the destruction of the Ribeira Palace.)

The saviour of Lisbon was the Prime Minister Sebastião de Melo, later ennobled as the Marquis of Pombal. His immediate task was to “bury the dead and heal the living” but important decisions were to be made about the future of the city. Should it be abandoned, rebuilt with scavenged material, or levelled and rebuilt from scratch? It was the latter course that was adopted. The dark, narrow and winding streets of medieval Lisbon were gone, and a beautiful new central Lisbon emerged with wide streets laid out in a grid, spacious squares and a handsome neoclassical architecture that came to be known as Pombaline. These new buildings were designed to be earthquake-proof, one of the earliest attempts at anti-seismic building; many of them were pre-fabricated outside the city and moved quickly into place.

Though Lisbon was confidently rebuilt, the disaster seems to have shaken European philosophy as well. Voltaire used the catastrophe to mock the optimism of Leibniz and Pope, asking “And can you then impute a sinful deed/ To babes who on their mothers’ bosoms bleed?/ Was then more vice in fallen Lisbon found,/ Than Paris, where voluptuous joys abound?/Was less debauchery to London known,/ Where opulence luxurious holds the throne?” Kant and Rousseau also weighed in on the subject.