1940 End of the Battle of Britain

In June of 1940 as the armies of Nazi Germany sprawled triumphantly across western Europe, Prime Minister Winston Churchill spoke to the House of Commons:

What General Weygand called the Battle of France is over. I expect that the Battle of Britain is about to begin. Upon this battle depends the survival of Christian civilization. Upon it depends our own British life, and the long continuity of our institutions and our Empire. The whole fury and might of the enemy must very soon be turned on us.

Hitler knows that he will have to break us in this Island or lose the war. If we can stand up to him, all Europe may be free and the life of the world may move forward into broad, sunlit uplands. But if we fail, then the whole world, including the United States, including all that we have known and cared for, will sink into the abyss of a new Dark Age made more sinister, and perhaps more protracted, by the lights of perverted science.

Let us therefore brace ourselves to our duties, and so bear ourselves that if the British Empire and its Commonwealth last for a thousand years, men will still say, ‘This was their finest hour.’

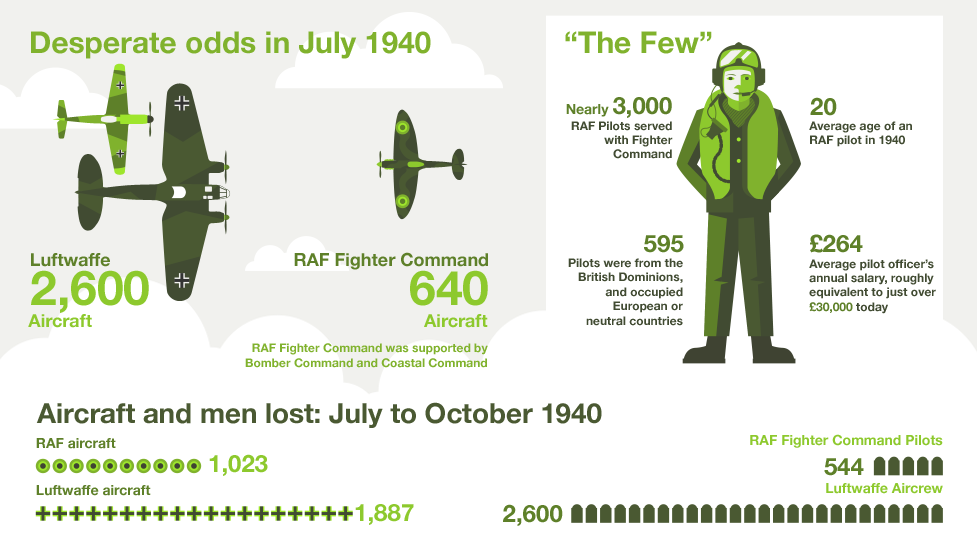

The Battle of Britain, which was to prepare for a sea-borne invasion of England, was entrusted by Adolf Hitler to the Luftwaffe, his airforce. The plan was to secure a safe crossing of the Channel by wiping out the possibility of resistance by the Royal Air Force. RAF squadrons were to be lured to the sky or destroyed on the ground by the veteran pilots of the Luftwaffe who had successfully destroyed the airforces of Poland, France, Belgium, Norway and the Netherlands. Once the RAF was out of the way, bombing of cities would destroy the British economy and morale and pave the way for an easy invasion. The ineffective performance of the RAF in the skies over France gave Field Marshal Hermann Goering much optimism.

For months in the summer and autumn of 1940 thousands of missions were flown against Britain. Though the RAF was outnumbered, it possessed two excellent fighter craft, the Hurricane and the Spitfire, manned not only by British crews but exiles from Nazi Europe and volunteers from the Commonwealth. Radar intelligence gave the defenders a look at their attackers as they formed up and advanced. It was a close run thing. On October 31, the Luftwaffe abandoned the attempt to destroy the RAF and abandoned plans for an invasion. The Battle of Britain had ended and the Blitz — the attack on British cities — would begin.