1054

The Great Schism Begins

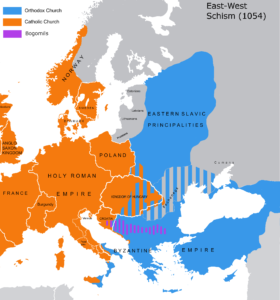

The Eastern and Western branches of Christianity had been growing farther apart over the centuries. Though they were in theory one Church, a number of factors had resulted in the development of separate worldviews and liturgical practices. The Eastern church thought and wrote in Greek, a language of which the Latin-speaking churchmen of the West were largely ignorant. The West demanded a celibate clergy; the East allowed priests (but not monks) to marry. The two churches quarrelled about the proper system for dating Easter and whether leavened or unleavened bread was to be used in communion. For Westerners the Bishop of Rome was the undisputed head; Easterners, under the thumb of the emperor in Constantinople, tended to regard the pope’s supremacy as only one of respect. Rome looked to the semi-barbarian kingdoms such as those of the Franks or the Germans for political muscle; Constantinople looked to convert the Slavs and orient them to Constantinople. Even theologically there were quarrels, especially over whether the Holy Spirit proceeded from the Father and Son (as in the Western creed) or only the Father (as in the East).

Matters came to a head in 1054. In the previous year Byzantine churches in southern Italy were harassed by papal authorities and Michael Keroularios, Patriarch of Constantinople, had closed Western churches in the capital. Anti-Western riots broke out in Constantinople before two legates arrived from Rome carrying a document signed by Pope Leo IX seeking military aid from the emperor and his help in curbing Keroularios who had termed Western clergy as “dogs, bad workmen, schismatics, hypocrites and liars.” Though they received a friendly reception from emperor, relations with the Patriarch grew heated. On July 16, the Roman emissaries laid a bull of excommunication against the Patriarch and his supporters on the altar of Hagia Sophia, and four days later Keroularios excommunicated the Roman legates. At the time, this was seen as being of little importance. The pope had died in April, rendering the commission of the delegates invalid; the Patriarch’s excommunication only extended to the Roman diplomats personally. But as time went on the split, later called the Great Schism, only widened and mistrust grew. In 1204 the sack of Constantinople by Catholic crusaders left a scar on the body of Christendom that has still not healed, though attempts have been made by Pope John Paul II, Francis I, and the Patriarchs of Constantinople and Moscow to heal the split.