1377

English heretic John Wycliffe is condemned by Pope Gregory XI

John Wycliffe (or Wyclif) (1331-84) was an English priest during the time of the Babylonian Captivity, when the papacy removed itself from Rome to the town of Avignon. There, under the severe influence of the French king and a series of French popes, the Bishop of Rome lost much respect in the eyes of believers. Coupled with high-ranking corruption and the devastation caused by the cataclysmic Black Death, the discredited Church lost ground to a number of wide-spread heresies. Among these dissident groups was one called Lollardy which sprang up in England in response to the teachings of Wycliffe.

Wycliffe’s ideas were strongly opposed to many fundamentals of the medieval Church. They included a belief in predestination and the notion of an invisible church — that the true believers constituted the real Church as opposed to its visible hierarchy. The earthly Church should be a poor one and relinquish its vast land holdings; it should abjure the doctrine of transubstantiation and possess scripture in the common tongue of the people. Perhaps most radically, Wycliffe proposed in his book On Civil Dominion that clergy in a state of sin could not hold dominion, an idea that conceivably could also be applied to secular rulers.

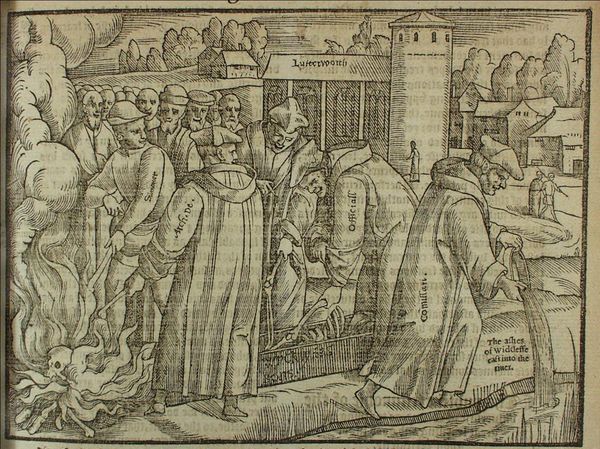

On May 22, 1377 Pope Gregory XI, the last pontiff of the Babylonian Captivity, condemned 18 propositions found in On Civil Dominion, sending copies of his bull to England where he expected it to be enforced. Wycliffe, however, had strong political protection from English political magnates such as John of Gaunt who favoured the notion of a politically-emasculated Church. He was able to live out his life relatively untroubled by prosecution but when his ideas were preached during the 1381 Peasant Rebellion, Lollardy fell from favour. In 1428 Wycliffe’s body was exhumed by the order of the pope, burnt and thrown into the river (see above).