553

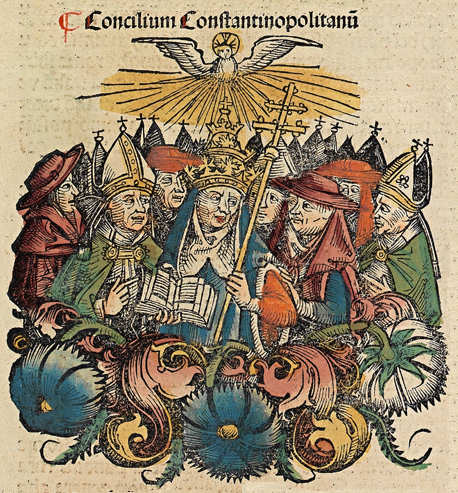

The Second Council of Constantinople

There was nothing that Christians of the East liked better than arguing about the nature of Christ and by the 500s Christianity had developed three great strains of thinking on the subject. All agreed that our Lord possessed two natures — human and divine — but there was disagreement as to the relationship and balance. In Egypt and the Levant, the Monophysite position predominated: that the divine nature of Christ almost obliterated the human aspect. In Persia and middle Asia, Christians of the Nestorian variety thrived; they stressed the human side of Christ’s nature and denied that Mary could be called “Theotokos” or “God Bearer”. In the West and Asia Minor, the Chalcedonians believed in a “hypostatic union” where the human and the divine coexisted simultaneously: Jesus Christ, one Person, fully God and fully man.

The Second Council of Constantinople was called at the urging of the Emperor Justinian who hoped that a condemnation of some earlier writings tainted with Nestorianism would help heal the gap between Monophysites and Chalcedonians. In fact, division was exacerbated by the meeting. The pope objected to the fact that the Council had been called without his authorization and he had doubts that the writings in question were really all that heretical. Western bishops found themselves unable to debate intelligently because the knowledge of Greek had largely disappeared among western churchmen. The result was further schism, more excommunications and no reconciliation.

The failure of Constantinople II was to lead to further theological hair-splitting such as monoenergism and monothelitism — Christ had two natures but only one energy or one will. These two would fail to find common ground.