‘Tis prophecied in the Revelation, that the Whore of Babylon shall be destroyed with fire and sword and what do you know, but this is the time of her ruin, and that we are the men that must help to pull her down?’

John Rogers, 1657

‘A thing that never was heard of, that so few men should dare and do so much mischief.’

Samuel Pepys, 1661

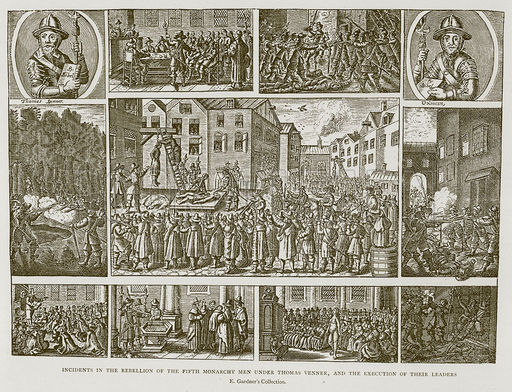

On this day in 1661 Thomas Venner was executed in London for treason, suffering the usual punishment of traitors: being hanged, drawn and quartered. He had led a rebellion against the English government in the name of the Fifth Monarchy, violently rampaging through London before being cornered in a tavern and his men shot to pieces.

The English Civil War of the 1640s had pitted defenders of the Stuart monarchy against supporters of a Puritan-dominated Parliament. The chaos engendered allowed a number of extravagant fringe movements to develop: “Ranters”, amoral pantheists who found virtue in blasphemy; “Levellers” who wanted an end to social distinctions; and agrarian socialist “Diggers”. Among the most radical were the believers in the Fifth Monarchy, an idea taken from the Book of Daniel where King Nebuchadnezzar dreamt of a final kingdom that would last forever. They were millennialists, confident that the End Times were near and they hoped to set up an English theocracy before witnessing the conversion of the Jews and Moslems and the return of Christ. Some Fifth Monarchy Men were hoping to accomplish their goals peacefully but others such as Thomas Venner, a London cooper, were prepared to use force to overturn the government. In 1661, hoping to prevent the re-establishment of the Anglican Church and the Stuart monarchy he led an uprising of a few hundred men under the slogan “King Jesus and the heads upon the Gates”. For a few days they controlled parts of London before being trapped and overcome by regular army troops. Wounded 19 times, Venner was placed quickly on trial and executed with other of his surviving men.

The Fifth Monarchy movement abandoned its violent wing and continued to press for reform and hope in the Second Coming well into the 18th century.